The failure of The Gravel Institute

An informal exploration of left and right-wing media

On September 28, 2020, an American nonprofit known as The Gravel Institute released its first video the year after an unsuccessful presidential campaign from its namesake, the late Senator Mike Gravel. Outlining its intention to fight right-wing disinformation through left-wing YouTube videos, it singled out the much larger conservative organization PragerU as its primary enemy due to its significant media presence and vowed to defeat it at its own game. The subsequent war started off strong. A little over a month after its first informational video, which addressed conservative talking points on big government, The Gravel Institute had both a six-digit view count on the video and a six-digit subscriber count. Unfortunately, this success was not one to last.

Less than three years after it entered the public eye, The Gravel Institute has come to a standstill. Its YouTube channel has been inactive for about a year since the time I am writing this. Its once-aggressive Twitter posts have been replaced by occasional retweets. And lastly, as confirmation of the nail being in the coffin, its official website shut down with little notice in July. At the same time, PragerU remains alive and thriving. Less than a week after the Institute lost its website, PragerU’s children’s content was officially approved for use by Florida’s Department of Education, continuing the trend of right-wing radicalization within the state. While the Institute’s goal was to outlive PragerU, it was ultimately outlived by Henry Kissinger.

Seeing as how the initial excitement around it amounted to failure in the end, I want to break down why I think The Gravel Institute was unsuccessful, with each point roughly being ordered by the organization’s fault. While little can be done about circumstances beyond the Institute itself, I believe that it practically set itself up for failure through its project execution alone and want to offer suggestions that others could use in the future. Analyzing and learning from its downfall will hopefully lend to smarter efforts against right-wing extremism, protecting children and other impressionable individuals from harmful beliefs.

The elephant in the room

Acknowledged from the start by its founders, by far the greatest obstacle in the face of The Gravel Institute was its difference in funding relative to PragerU. Although both organizations derive their budget from donations that typically come from individuals, PragerU has an inherent advantage by being older and conservative. The wealthy have no incentive beyond altruism for supporting The Gravel Institute since its advocacy for wealth redistribution suggests they will be stripped of some of their power, whether it be quality of life or political influence. On the other hand, PragerU protects the wealthy by advocating for the opposite. Even from a non-economic standpoint, its opposition to modern social justice movements like Black Lives Matter can exacerbate prejudice among struggling individuals and impede the development of working-class solidarity across demographic lines. With an ideology that conveniently courts wealthy Republicans, PragerU had a reliable donor base that included the likes of Dan and Farris Wilks, two homophobic billionaries who provided most of its initial funding.

PragerU’s annual budget sat at an estimated $28 million during The Gravel Institute’s founding in 2020. In 2022, the last year that saw a Gravel Institute video, this budget more than doubled to $65 million. With millions of dollars already available for PragerU to scale operations, any attack that flanks them from the political left can only be an uphill battle. The Gravel Institute may have been able to release a video every few weeks with the help of Patreon, but bimonthly content is far from enough to become mainstream like PragerU.

Unmeasured and untested

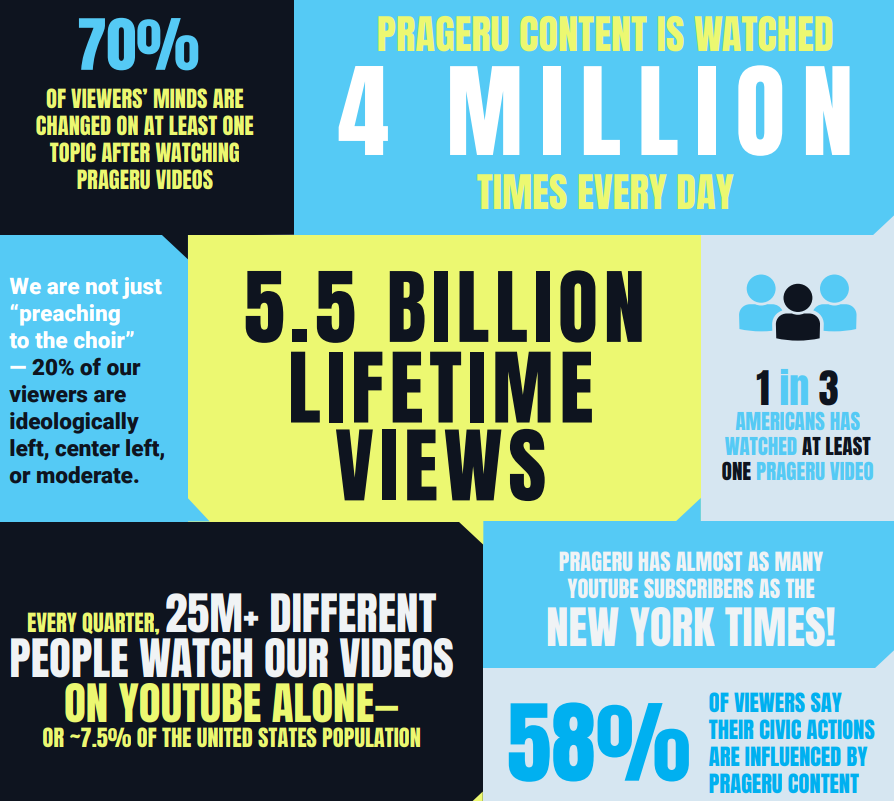

A concern I had during the heyday of The Gravel Institute was that its content might not prove effective at politically influencing people—there is no way to tell if people do not report how their beliefs have changed as a result of watching. On the other side of the political spectrum, PragerU avoids this by having a marketing and analytics team. Biannual reports provide statistics on its raw numbers and percentages of its audience that meet important conditions. In its 2022 report, PragerU reported that 58 percent of its viewers were influenced as citizens and a larger 70 percent changed their beliefs as a result of watching. It continues by responding to echo chamber accusations, citing a fifth of their viewership being to their left and a third of all Americans having watched one of its videos at some point.

At this point, it is important to bring up the inherent bias of a political organization conducting surveys of its own influence. We do not know the methodology PragerU used to reach the data it shows in the reports, and we do not know whether statistics were manipulated slightly for the sake of presentation. On the side of the respondents, people may feel pressured to respond in a certain way given the wording of a question or the knowledge that PragerU itself is behind the surveys. However, even if PragerU’s influence statistics are illegitimate, its massive media presence effectively allows others to report progress for them. YouTube video essays express concern over the alt-right pipeline it creates. People provide anecdotes of their relatives being radicalized. In terms of empirical evidence, social scientists have thoroughly analyzed the impact of right-wing media. As long as the literature demonstrates it can be effective at meeting its goals, PragerU will know what to do.

Unfortunately for The Gravel Institute, there exists a significant lack of name recognition and funds that make it difficult for them to evaluable their adherence to goals. Social scientists are unlikely to comment on it if they do not consider it a major organization while budget constraints prevent internal evaluation from happening without tradeoffs. The most that can realistically be maintained is highlighting anecdotes from people the Institute helped through its content—heartwarming for a YouTuber, but not nearly as assuring for an ambitious organization.

No conversation

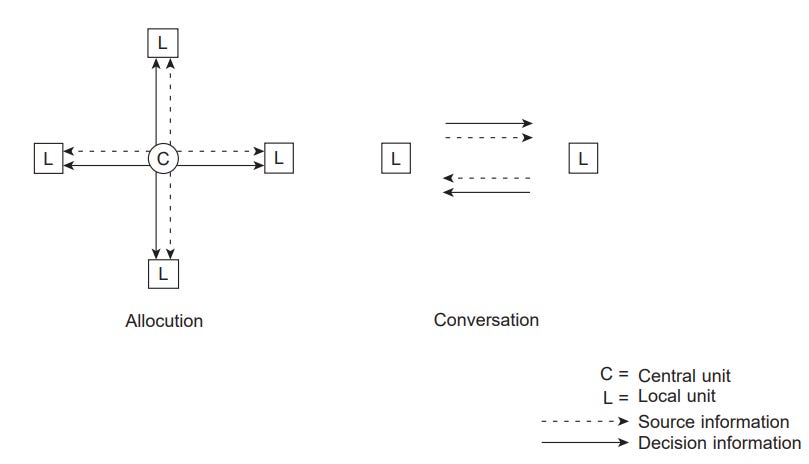

(Image adapted from The Network Society, by Jan van Dijk.)

Despite basing itself largely on two social media platforms, The Gravel Institute did little beyond its informational videos when engaging with its audience—interaction comes across as an allocution from teacher to student rather than an educational conversation between the two. While some attempt at engagement was made by offering video calls between the organization’s staff and donors, this came at a hefty price of 100 dollars per month on Patreon. With a monthly minimum of five dollars for perks, even access to the Institute’s Discord server was paywalled, leaving the majority of viewers nothing but Twitter and the YouTube comments section. This limits conversation not only in quantity, but its quality with respect to the Institute’s vision. If someone regularly donates to a political project, it is reasonable to assume that those supporters have similar political leanings or an ideology that believes in platforming those politics. The Gravel Institute spoke boldly of pushing people left but simultaneously limited discussion to patrons who likely already made it. I doubt those conversations would be pointless since leftists can still discuss strategy with each other, but by design alone, they fail to include viewers with the heaviest criticisms and questions. As a worst-case scenario, I believe the Institute could have operated like an echo chamber where it repeatedly works based on the reactions of its political allies—progress dies to the positive feedback loop.

I personally avoid content produced by PragerU since its ideology gives me a feeling of unbridled disgust, but from what I know, it seems more effective at engaging its audience. Dennis Prager hosts “fireside chats” where he answers questions posed by viewers, which at least gives the impression that he cares about his audience. It is possible that those questions are cherry-picked to include primarily conservatives, but publishing Q&As alone signals there being a possibility of a viewer being heard. Prager demonstrates he is open for discussion in some capacity, and people from any background can treat that as an opportunity to ask questions.

Going back to the issue of funding, I do not think The Gravel Institute is entirely at fault for having poor engagement—Patreon alone cannot secure the hours required for staff members to find inquisitive viewers and produce additional content for their questions. Still, I maintain that more options could have been explored to accommodate the organization for discourse. Problems of weak discussion are better when they are not self-caused.

Infighting

Aside from funding, another unavoidable issue that plagued The Gravel Institute was the diversity of thought within leftism. On less economic issues like electoralism, authoritarianism, and foreign policy, people on the left sometimes disagree to the point where they reject each other’s identification as leftists. If conflicts as severe as these continue, it will become much harder for the left to network with others and secure the base they need to fight back. Someone who believes that voting is useless in a right-wing duopoly might not listen to someone who still believes in their ballot, and someone who sees China as an equitable socialist state may ignore someone who sees nothing but authoritarian capitalism.

However, while infighting is inevitable, a decision to engage is not—The Gravel Institute eventually cratered on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine since the Ukrainian side of the issue was far more popular than Russia’s. Downplaying the threat of an attack before the invasion occurred and even after the war had begun, it released a YouTube video that arguably fearmongered about Nazi influence in Ukraine. With American support for Ukraine being mainstream among both centrists and leftists, the Institute received enough backlash for it to purge its controversial Twitter posts and delete the video. Looking at the situation in the hypothetical, the alternative outcome would have been far preferable but still far from ideal. If the Institute decided against publishing the video for their reputation’s sake, abiding by that decision would have left an important topic taboo in the eyes of its audience. People are forced to find other sources to inform themselves, which can lead them to competitors like PragerU.

While disagreement does exist between conservatives, there is considerable agreement on social issues that facilitates networking between media figures. According to sociologist Francesca Tripodi, PragerU’s networking efforts not only allow its audience to hear from conservative voices like Ben Shapiro and Dave Rubin, but also white supremacists like Stefan Molyneux. Knowing that Dennis Prager has spoken with Rubin and Rubin likewise with Molyneux, people are at best two degrees of separation away from consuming blatantly racist content when they decide to extend their viewership from PragerU. Outperformed in terms of networking, The Gravel Institute fought an uphill battle that became truly insurmountable once they provoked their own allies.

Lofty promises

As a way to maintain their viewership while fighting against PragerU, The Gravel Institute had to promise content that was either eye-catching or directly beneficial to the viewer. The former, which involved recognizable presenters in each video, seems to have fallen short. While presenters like Marianne Williamson and Robert Reich do have respectable name recognition as a presidential candidate and former Labor Secretary, respectively, the Institute’s YouTube channel description specifically mentions Bernie Sanders and Chelsea Manning as examples of presenters. Continuing a year-long silence on its channel, it has yet to release a video where one of those two are featured as the presenter. People who disagree with figures like Sanders and Manning may have a stronger willingness to hear them out in the Institute’s video format. A libertarian who sincerely believes in a marketplace of ideas, for example, could gain much more in five minutes compared to the seconds spent on a Twitter post or CNN soundbite. Two years without delivering on said content, however, prevents that valuable engagement from happening and puts the organization’s reliability into question.

As alluded to from my discussion on conversation, The Gravel Institute also offered its viewers direct benefits through perks for Patreon supporters. Since I am not a patron and lack access to the organization’s Discord server, I cannot speak on whether those benefits were consistently fulfilled during its period of activity. However, what I do know is that the Institute has yet to disable monthly donations via Patreon, a decision some of its Facebook followers noticed with frustration. People are not being scammed if they are voluntarily donating through a seemingly indefinite period of inactivity, but it is a serious problem if they keep donating out of a lack of awareness. The Institute’s promise above all else was content, but now accumulates funds without keeping its own end of the bargain. Even if it returns, I cannot imagine the hurdles required for it to recover.

Hostile branding

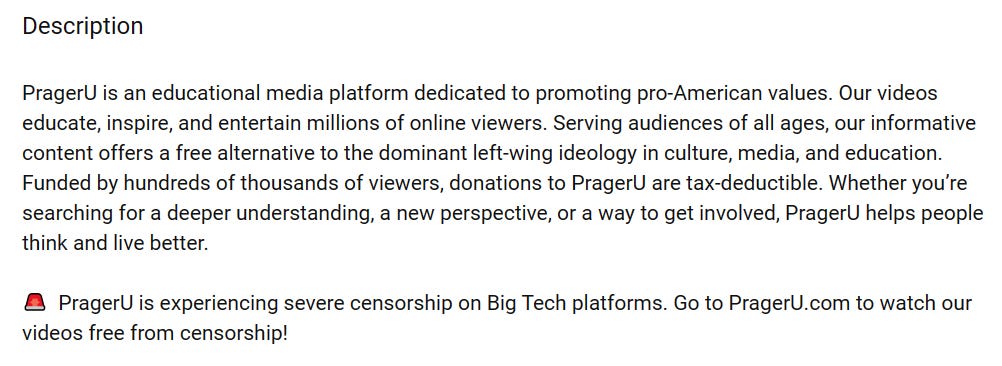

Lastly, to illustrate why I now believe The Gravel Institute doomed itself from the start, I want to provide a screenshot of its YouTube channel description to compare it with the description of PragerU:

What immediately stands out with the Institute’s statement is its aggression—PragerU is a rich and powerful enemy that needs to be knocked from its pedestal by a leftist underdog. Although I personally agree with the sentiment, I do not believe that level of partisanship would be palatable to the percentage of Americans who need to hear it most. In the chance that someone finds The Gravel Institute before they find PragerU, it would likely prompt them to visit the latter’s channel and find that based on its own channel description, the Institute put out a mischaracterization.

Unreflective of its far-right affiliations, PragerU’s channel description comes off as good-faith, if not neutral, diverging significantly from the claims of propaganda. While it does characterize leftism as being dominant, content itself is described as a "free alternative” to it rather than a necessity in a fight against evil. Someone unfamiliar with the channel could easily interpret this as encouraging new ways of thinking and would quickly be corroborated by the second half of the paragraph. “Pro-American values” are also neutral in the context of political influence. While beliefs like American exceptionalism and imperialism are common among staunch conservatives, stretching them to fit the label of “pro-America” will inherently appeal to people who live in the United States. Opposing the country’s well-being is self-destructive and reduces everyone’s quality of life, so supporting the country must be universally good. Other than a censorship issue it addresses by linking its own website, PragerU comes across as a well-meaning educational project started by patriotic moderates, priming them to capture a moderate audience.

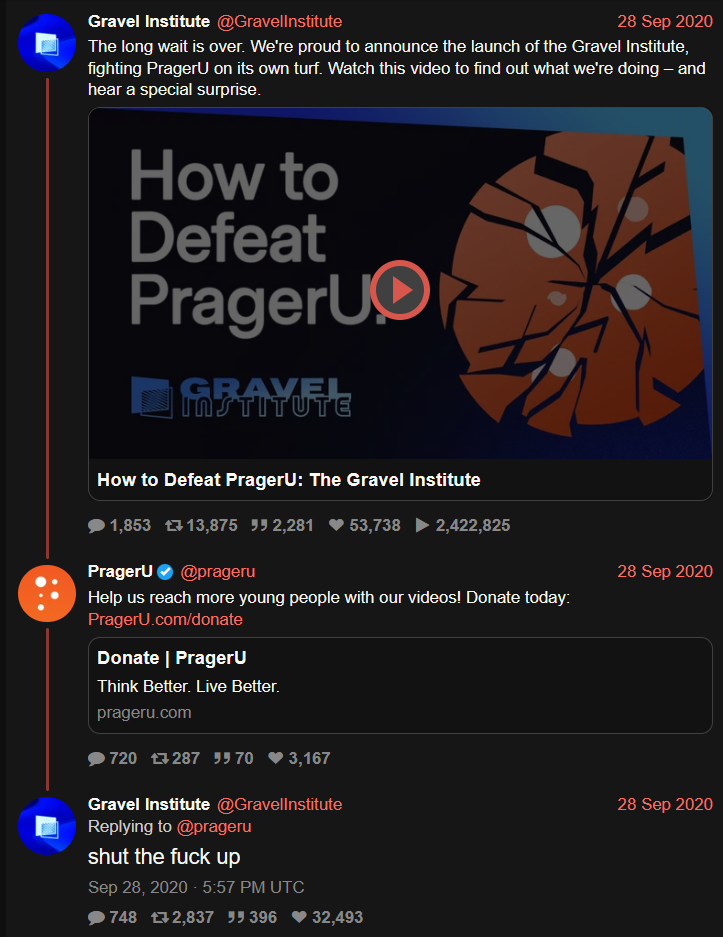

It seems more likely for Gravel Institute viewers to have found PragerU than vice versa due to the former mentioning the latter by name, and combining this with the organizations at face value, the Institute ironically presented itself as the unreasonable one. Even from this position, however, people looking deeper into the feud could further PragerU’s advantage. Because the Institute generated significant media attention when it started, a single fundraising tweet in the replies of its launch video secured valuable exposure for PragerU, as shown above. While the numbers alone indicate a devastating ratio, Twitter is far from real life. PragerU almost certainly collected donations in the process of getting piled, and since The Gravel Institute was on the offensive, newly galvanized conservatives could have matched this aggression with their own money.

Additionally, since the Institute has Twitter posts from its presidential campaign days and content from after its launch, people had material to scrutinize while it was in the spotlight. Titles like “Why America Sucks at Everything” and ones that highlight socialism already feel malicious to people who grew up hating Cold War communists, immediately making them distrustful. The Institute’s Twitter history from 2019 to 2020, however, sounds the death knell for discourse. David Oks and Henry Williams, the then-teenagers who persuaded and effectively controlled Gravel’s presidential campaign, repeatedly cursed out moderate Democrats using the senator’s verified account and continued dragging people even after the Institute’s launch. While this did provide entertainment value, people knowing about the Institute’s past as a hyper-aggressive Gen-Z vanity campaign makes pivoting to a persuasive source of progressive education completely unfeasible. Moderates and the politically unaware will not listen in good faith when they are attacked at a personal level, and for that reason, I doubt The Gravel Institute even had a chance.

The future of the fight

As things currently stand, The Gravel Institute is dead and PragerU is currently thriving without any institution to challenge it. If another organization eventually rises up for the challenge, I offer these suggestions that I hope it will pick up organically:

If possible, reallocate resources toward audience engagement. Budgets are inevitably going to be tight relative to PragerU, but starting conversations with viewers of all backgrounds demonstrates a sincere belief in progressive ideas and a stronger commitment to education. Retaining viewers through reliable methods of engagement can also prevent the alt-right from courting them.

Don’t overpromise, and provide transparency when things fall short. Once again, retaining an audience of learners is crucial against competition like PragerU, and being honest about the state of the organization builds the trust necessary for retention.

Don’t say the opposition’s name. By growing an organization that openly works in opposition to another, people may be repulsed by the possibility of aggressive partisanship. If someone is conservative or sits on the fence over what to believe, they may funnel more resources into right-wing organizations if they perceive that the left is grossly mischaracterizing them.

Accommodate people and fit ideas to their worldview. Since people in the target audience would not take kindly to a stranger aggressively shaming them for incorrect beliefs, it would help to consider where they are coming from and advocate for better beliefs within that context. To provide examples, people who value individualism may be swayed if unions and cooperatives are framed as methods of securing individual power in the workplace. People who support traditional family values will see more value in social safety nets if they understand their coverage of basic needs, incentivizing the growth of families. People who blame marginalized groups for their struggles may mellow out if tolerance is explained as a way to avoid needless conflict and build solidarity among workers. As long as an awareness of other people’s beliefs is maintained, there are better odds of them listening.

Encourage sharing content at an individual level. Since some people will still be beyond the organization’s reach due to weak funding or a distrust of leftism, the onus must be on proactive individuals to win the rest over. While discussing politics with another person is undoubtedly daunting for many, an advantage exists in that people will likely trust someone reputable from their personal network over an organization or stranger they do not know.

It is difficult not to scream about politics. No platform, digital or physical, is safe from cartoonishly horrendous political takes that leave you wondering how your country is still standing. However, as cathartic as dragging people on Twitter may feel, we still need to get better as a society. When the time demands it, we will need to rip the bandage off and have that quieter conversation.

I know we can do better than PragerU, and whatever comes next has past mistakes to learn from. Best wishes to them as they figure out Florida.