As someone who believes the mainline Pokémon games have suffered transitioning to the newer consoles, I was not a fan of Pokémon Sword and Shield—the thought put into the design of the Galar region failed to translate to elements like animation and made for a rushed product. A cutscene I found particularly egregious was the introduction of Piers. While the literal animation of the models was passable, one conscious omission by the developers at Game Freak made the scene impossible to take seriously. You can watch it below in all its infamy.

Piers has all the diegetic elements he needs to start singing or rapping: an instrumental, a punk atmosphere, and a vocal audience of Team Yell grunts. These elements come together to make it agonizingly awkward when he performs without saying a word. The audible sounds he instead makes by swaying and tapping his foot hammer the final nail into the coffin, forcing a respectable artist to play charades.

Realizing how important it is for 3D animation to cohere with sound, Pokémon fans have used the Piers debacle to advocate for voice acting in future Pokémon games. Having suffered through the scene myself, I think this is an agreeable sentiment. As I’ve touched on in my writing about the Generation V Pokémon games, working in three dimensions is difficult since it raises the bar for realism. Unless Pokémon makes a highly unlikely decision to return to the iconography of its DS-era games, the franchise will need to do far more than usual to keep its world immersive. On the other hand, I believe critics (including myself) have overlooked how voice acting would jeopardize a quintessential design element from the mainline games. If Pokémon fans truly believe the games will improve by giving characters their own voices, they must be willing to exclude themselves from the narrative and return control to the director.

You are the trainer

Players are included in the narrative of every mainline Pokémon game by virtue of their customization—each one allows at least a name and gender to be determined for the protagonist and replaceable nicknames for native-caught Pokémon. On the surface, this benefits the player as a consumer. Players enjoy representing themselves in game since they get to play for their own tastes or feelings of accomplishment. When you name the protagonist after yourself, for example, accomplishments like becoming Champion and completing the Pokédex are correctly praised as feats of your own. The protagonist never exists beyond pixels on a screen, but you physically pressed buttons until your name showed up in the Hall of Fame. The protagonist catches and nicknames Pokémon the way they do since they are no more than an output for your own desires—you are the trainer incarnate.

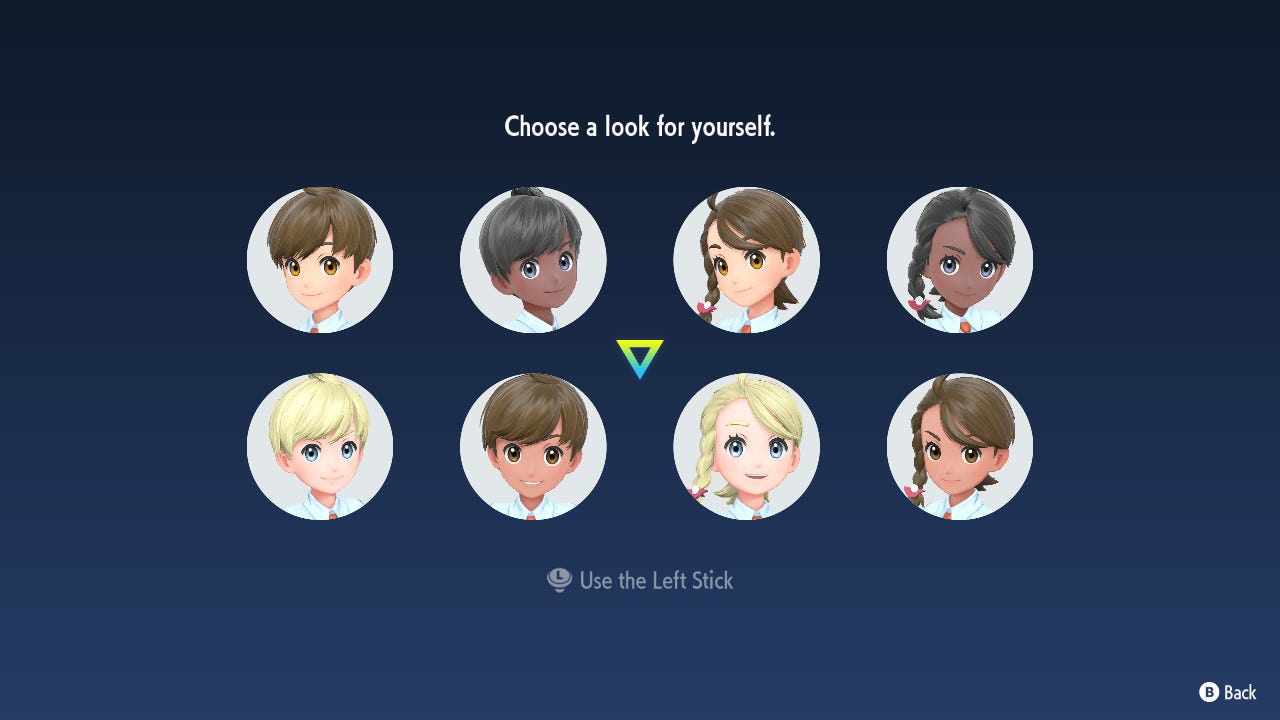

On the other side of the transaction, a high demand for self-representation benefits Game Freak as a producer and incentivizes them to structure the franchise around it. In a political landscape urging media representation for historically marginalized groups of people, Pokémon games have made major strides since Generation I by sequentially introducing gender, attire, and skin tones—all features that allow protagonists to look convincingly like the players piloting them.

(As a side note, The Pokémon Company’s commitment to inclusion only goes as far as their bottom line allows them to—every Pokémon game that allows gender customization imposes an immutable gender binary and only implies queer representation since the franchise unfortunately sells in queerphobic countries.)

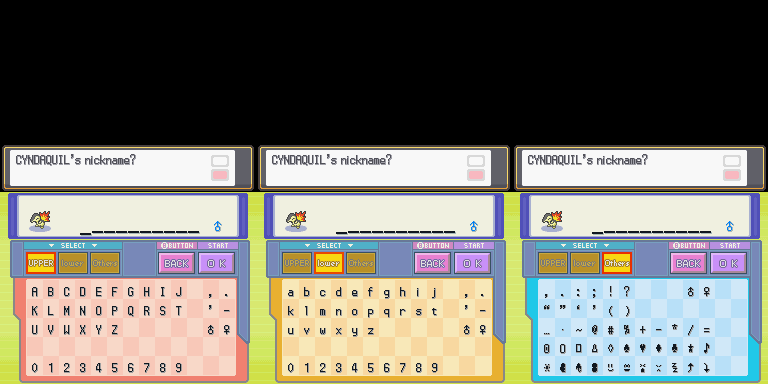

You are the problem

As much as player representation rationalizes customization, its most longstanding forms in the Pokémon games present an obstacle to both voice actors and developers specifically because you get input as a player. If they aren’t expected to perform lines verbatim, voice actors typically need some certainty of what exists in the fictional universe they are contributing to. This becomes impossible knowing there are virtually infinite names that would also have to be pronounced the way they are intended to. Even if this obstacle could be surmounted through means like generative AI (which raises questions about artistic integrity and capitalism), it could struggle to abide by hardware constraints. The amount of data required to voice every possible name seamlessly into the game would blow past the gigabytes, making it impossible for physical releases of the game to continue at regular production costs. Pokémon games can certainly still have voice acting (as evidenced by Pokémon Battle Revolution having lines for every species name up to Generation IV), but Game Freak cannot fully accommodate what is inherently beyond their control. The options are limited when you involve yourself as a player.

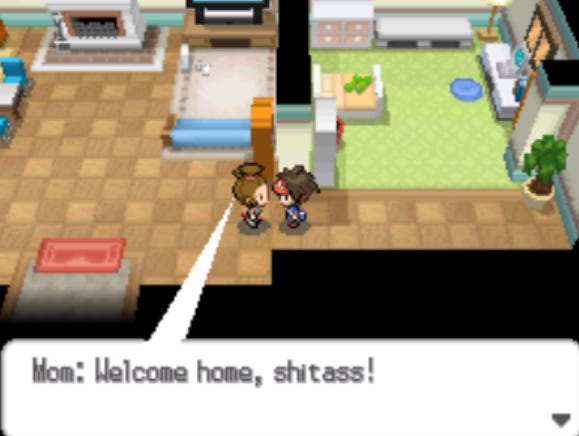

Logistics aside, any attempt at combining voice acting with customization in the Pokémon games also compromises how compelling their narratives can be since names can easily be used as jokes. In fairness to proponents of voice acting, this has been a recurring problem in unvoiced Pokémon games. Every opportunity where you get to submit text of your choice, whether that be naming yourself, your rival, or your Pokémon, creates opportunities for something ridiculous or vulgar to display in game. However, when considering claims that it would make for a “serious” game, voice acting would still be undermined by the unseriousness of customization and exacerbates it whenever customizations are voiced. With the additional requirement of voice acting, what was once a self-gratifying joke on your part would become a hard-coded, multimodal part of the game—an endorsement of your intentions. You gain unprecedented directorial control of the game, and that makes you a problem.

You are the many

Some Pokémon fans may insist that proper voice acting would raise the bar for the franchise, but the same fandom they partake in makes it difficult to determine whether that’s even the case. Game Freak can only use one set of voice actors when they have an audience of diverse tastes to satisfy—some players may be thrilled with the voice direction while others may feel repulsed enough to put down the game. They could hypothetically allow players to switch out voice actors to avoid unfavorable matchups, but doing so would cost them both their money and directorial conviction. If voice acting is meant for people to take Pokémon seriously, allowing it to be replaced does the opposite by making the player decide what is canon for the director.

On the other hand, the unvoiced status quo of the Pokémon franchise functions surprisingly well from a narrative perspective since it creates a natural stopping point for players to develop and propagate their own canon—you build off the director’s work instead of finishing it for them. Attempting to impose voice acting over this dynamic is actually a hindrance since it forces you to parse through the director and voice actor’s interpretation without providing you space for your own. For any professional Let’s Play of a game with dialogue, the player will read the dialogue in a voice they deem fitting if the character itself is not voiced. When the character is voiced, the player will wait for them to finish and move on. I’ve timestamped examples of both in their respective order below.

Your voice will decide

In Pokémon HeartGold and SoulSilver, Red stands atop the summit of Mt. Silver looking for a worthy challenger. He doesn’t say a word when you approach him to battle, yet he steals the show. Red is you from the prior generation of Pokémon games and speaks only in ellipses because Game Freak knows they know nothing about you. You fill in the gaps as to who Red is. You are the co-producer of the game—them giving Red any voice but yours is to deny who you are.

Times do exist in Pokémon where voice acting seems necessary. There is not much of an argument to be had with Piers, and the standards for realism in the market keep rising as console games reach new graphical heights. However, we need to understand that trusting Game Freak’s taste in voice actors requires us to subdue our own role in the production process for the better or worse. Pokémon is heavily driven by its community and video games are defined by human interaction—we should not lose sight of either.

Take a moment right now to battle Red. What do you want out of a game? Do you feel coddled or empowered by opportunities to represent yourself? Do you want to experience someone else’s narrative, or attempt to create your own?

Red doesn’t have much of a voice, but you do. Make sure to use it.